In all their suffering he also suffered, and he personally rescued them. In his love and mercy he redeemed them. He lifted them up and carried them through all the years. But they rebelled against him and grieved his Holy Spirit. So he became their enemy and fought against them. [Isaiah 63:9-10 (NLT)]

Many years ago, my two boys were playing at their grandparents’ house. While Grandpa worked in the garden, the brothers climbed up into the apple tree and started to throw apples at him. A patient man, their grandfather told them to stop and, when more apples came whizzing at him, he offered a sterner warning. After briefly stopping their barrage, the rascals were unable to resist the temptation and chucked more apples at Grandpa. To their surprise, this gentle and loving man turned around, picked up some apples, and returned fire. Having played ball as a boy, Gramps had a strong throwing arm and excellent aim. He didn’t pull any punches as he pitched those apples back at his grandsons. The boys, unable to maneuver easily in the tree, quickly learned the meaning of “as easy as shooting fish in a rain barrel.” When they called, “Stop, Grandpa, it hurts!” he replied, “Yes, I know it does, but you needed to learn that!” It wasn’t until those hard apples hit their bodies that the youngsters understood how much their disobedience hurt their grandfather (both physically and emotionally).

Many years ago, my two boys were playing at their grandparents’ house. While Grandpa worked in the garden, the brothers climbed up into the apple tree and started to throw apples at him. A patient man, their grandfather told them to stop and, when more apples came whizzing at him, he offered a sterner warning. After briefly stopping their barrage, the rascals were unable to resist the temptation and chucked more apples at Grandpa. To their surprise, this gentle and loving man turned around, picked up some apples, and returned fire. Having played ball as a boy, Gramps had a strong throwing arm and excellent aim. He didn’t pull any punches as he pitched those apples back at his grandsons. The boys, unable to maneuver easily in the tree, quickly learned the meaning of “as easy as shooting fish in a rain barrel.” When they called, “Stop, Grandpa, it hurts!” he replied, “Yes, I know it does, but you needed to learn that!” It wasn’t until those hard apples hit their bodies that the youngsters understood how much their disobedience hurt their grandfather (both physically and emotionally).

This is one of my boys’ favorite stories about their grandfather. Rather than being angry that he hurled those apples back at them, they’re proud of him. Knowing he loved them enough to discipline them, they learned a variety of lessons that day and not just that being hit by an apple hurts or not to be caught up a tree. They learned to listen to and obey their grandfather, that disobedience brings reckoning, and (after they picked up the apples) that obedience can bring rewards like apple pies. They also learned that their naughtiness grieved their grandfather as much as their punishment hurt them.

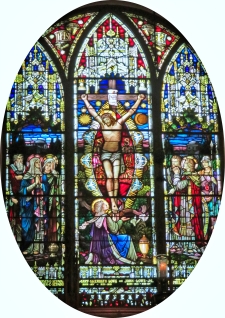

We know that Jesus experienced both physical and emotional pain when He walked the earth as a man but what did God the Father experience? As a spirit, without a nervous system, I doubt that He felt physical pain, but what about emotional pain as He saw His son rejected, suffer, and die? Does God have feelings? There are two opposing theological schools of thought about this question (the doctrine of impassibility vs. the passibility of God) and a whole lot of middle ground in-between. Not being a theologian, I’m not addressing doctrine.

Nevertheless, Scripture tells us that God can grieve and the parables of the missing coin, prodigal son, and lost sheep also tell us that God can rejoice. Throughout the Bible, we find examples of God expressing emotions like love, joy, compassion, hate, jealousy, anger and grief. Like any parent, God’s heart is touched by His children; it seems that He can feel our pain and that we can cause Him emotional pain.

Although Scripture tells us that God is compassionate and gracious, slow to anger and abounding in love, like the boys’ grandfather, God eventually will get angry. Moreover, Scripture shows us that our disobedience aggrieves our heavenly Father as much as an apple on the noggin and my boys’ defiance hurt their grandpa. When we disobey God, disgrace His name, doubt His love, forsake our faith, reject His guidance, choose hate over love or callousness over compassion, we bring sorrow, grief, and pain to God. Rather than bringing grief to God, may we always do what pleases Him, for it is in the joy of the Lord that we find strength.

Making the point that wisdom is better than strength, the sage Agur spoke of the wisdom of ants, locusts, lizards, and sāphān. Often translated as badgers, rock-badgers, hyraxes, conies, or marmots, the animal’s exact identity is unknown but commentators suspect it to be the Syrian rock hyrax. Looking like a cross between a rabbit, guinea pig, and meerkat, these social animals gather in colonies of up to 80 individuals. Sleeping and eating together, they live in the natural crevices of rocks and boulders or take over the abandoned burrows of other animals.

Making the point that wisdom is better than strength, the sage Agur spoke of the wisdom of ants, locusts, lizards, and sāphān. Often translated as badgers, rock-badgers, hyraxes, conies, or marmots, the animal’s exact identity is unknown but commentators suspect it to be the Syrian rock hyrax. Looking like a cross between a rabbit, guinea pig, and meerkat, these social animals gather in colonies of up to 80 individuals. Sleeping and eating together, they live in the natural crevices of rocks and boulders or take over the abandoned burrows of other animals. The attackers march like warriors and scale city walls like soldiers. Straight forward they march, never breaking rank. They never jostle each other; each moves in exactly the right position. They break through defenses without missing a step. [Joel 2:7-8 (NLT)]

The attackers march like warriors and scale city walls like soldiers. Straight forward they march, never breaking rank. They never jostle each other; each moves in exactly the right position. They break through defenses without missing a step. [Joel 2:7-8 (NLT)] Pope Francis recently visited Singapore and, when speaking to young people at an interfaith meeting, he is reported to have said “All religions are paths to God.” After comparing the various religions to “different languages that express the divine,” he added, “There is only one God, and each of us has a language to arrive at God. Some are Sheik, Muslim, Hindu, Christian, and they are different paths [to God].” While the pontiff was encouraging interfaith dialogue, his words are troubling. I will not presume to know the Pope’s meaning or intention with his comments. Nevertheless, I find it important to address how the world understood the pontiff’s message.

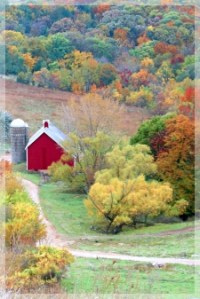

Pope Francis recently visited Singapore and, when speaking to young people at an interfaith meeting, he is reported to have said “All religions are paths to God.” After comparing the various religions to “different languages that express the divine,” he added, “There is only one God, and each of us has a language to arrive at God. Some are Sheik, Muslim, Hindu, Christian, and they are different paths [to God].” While the pontiff was encouraging interfaith dialogue, his words are troubling. I will not presume to know the Pope’s meaning or intention with his comments. Nevertheless, I find it important to address how the world understood the pontiff’s message. Because the pastor’s sermon was about being thankful, she’d selected “Come, Ye Thankful People, Come” as the evening’s opening hymn. Henry Alford wrote this hymn in 1844 for village harvest festivals in England called Harvest Home. Rural churches would celebrate the harvest by decorating with pumpkins and autumn leaves, collecting the harvest bounty, and then distributing it to the needy. Because of its seasonal harvest imagery, we usually sing this hymn in November at Thanksgiving but this was mid-July! Reading the hymn’s words out of their traditional Thanksgiving context, I understood their meaning in an entirely different way.

Because the pastor’s sermon was about being thankful, she’d selected “Come, Ye Thankful People, Come” as the evening’s opening hymn. Henry Alford wrote this hymn in 1844 for village harvest festivals in England called Harvest Home. Rural churches would celebrate the harvest by decorating with pumpkins and autumn leaves, collecting the harvest bounty, and then distributing it to the needy. Because of its seasonal harvest imagery, we usually sing this hymn in November at Thanksgiving but this was mid-July! Reading the hymn’s words out of their traditional Thanksgiving context, I understood their meaning in an entirely different way. In Sharon Garlough Brown’s novel, Two Steps Forward, a character choses to pray the Hebrew word hineni during Advent. When another character calls it a beautiful but “costly” prayer, I grew curious about this word. Hineni is composed of two little words, hineh and ani. By itself, hineh is usually translated as “behold” but, when combined with ani (meaning “I”), it usually is translated as “Here I am,” “I’m here,” or “Yes.” However, like shalom, the Hebrew hineni loses the depth of its meaning in translation.

In Sharon Garlough Brown’s novel, Two Steps Forward, a character choses to pray the Hebrew word hineni during Advent. When another character calls it a beautiful but “costly” prayer, I grew curious about this word. Hineni is composed of two little words, hineh and ani. By itself, hineh is usually translated as “behold” but, when combined with ani (meaning “I”), it usually is translated as “Here I am,” “I’m here,” or “Yes.” However, like shalom, the Hebrew hineni loses the depth of its meaning in translation.