This letter is from Paul and Timothy, slaves of Christ Jesus. I am writing to all of God’s holy people in Philippi who belong to Christ Jesus, including the church leaders and deacons. [Philippians 1:1 (NLT)]

Rather than introduce himself as an apostle, Paul often identified himself as a slave of Christ Jesus. In the New Testament, the Greek word doúlos is often translated as servant or bondservant but it clearly meant slave. Of course, with our 21st century mindset, we find the word “slave” abhorrent, especially when applied to us! The word’s use by Jesus and the epistle writers, however, was never an endorsement of involuntary servitude or thinking of people as chattel. Used as a metaphor, doúlos was an honorable word that applied to believers who, as devoted followers of Jesus, willingly lived under His authority.

Rather than introduce himself as an apostle, Paul often identified himself as a slave of Christ Jesus. In the New Testament, the Greek word doúlos is often translated as servant or bondservant but it clearly meant slave. Of course, with our 21st century mindset, we find the word “slave” abhorrent, especially when applied to us! The word’s use by Jesus and the epistle writers, however, was never an endorsement of involuntary servitude or thinking of people as chattel. Used as a metaphor, doúlos was an honorable word that applied to believers who, as devoted followers of Jesus, willingly lived under His authority.

Slavery was deeply rooted in the economy and social structure of the Roman Empire. With more than half the population either enslaved or having been slaves at one time, 1st century listeners and readers would have understood the metaphor in a far different way than we do today. Slavery could be voluntary and people often sold themselves into slavery to pay debts or simply because life as a slave was better than struggling to exist on one’s own. Hebrew Scripture even made provisions for an Israelite to sell himself (or a child) to pay off a debt. The law of manumission, however, allowed a slave to be freed once the debt was paid. As objectionable as the concept of slavery is to us, it was an everyday reality in the ancient world.

Rather than being repulsed at the concept of being a slave, let’s look at what Christian slavery means. Before becoming believers, we were slaves to sin. Jesus paid a ransom to God—one that freed us from sin, death, and hell. Rather than purchasing our freedom with silver or gold, it was purchased with His blood. Instead of becoming a slave to the redeemer who paid our financial debts (as would happen in the 1st century), we become slaves to the One who redeemed us by paying the price for our sins. In his use of the word doúlos in his letter to the Philippians, Paul is acknowledging that he and Timothy had been purchased with Christ’s blood and, as His slaves, they surrendered their will, time and interests to Him. Completely devoted to their Master—Jesus Christ—they were obedient to Him and subject to His command.

Belonging to his master, the slave has no time, will or life of his own and is totally dependent upon his master for his welfare. He is to be unquestioningly loyal and obedient and is obligated to do his master’s bidding with no regard to his own well-being. If that master were a man, such a situation would be horrendous. When the master is God—the One who made us and loves us as His own children—it is a good thing!

No Christian belongs to himself—we belong to our Redeemer. As His slaves, we choose to willingly live under Christ’s authority. We’ve been told that no one can serve two masters so we have a simple choice: be a slave to sin or a slave to Christ. Which will it be?

A few miles from our Illinois home, a giant ski jump towered over the treetops. Originally erected in 1905 by Carl Howelsen and a group of Norwegian skiers living in Chicago, it’s been rebuilt over the years and is still used today. In a curious coincidence, in 1913, the man who loved the mountains and deep snow found his way to the Colorado mountain town we once called our winter home. Although Howelsen returned to Norway in 1922, he left an indelible mark on the town by introducing it to recreational skiing and ski jumping. Not far from the hill named for him, stands a statue of the man known as Flying Norseman.

A few miles from our Illinois home, a giant ski jump towered over the treetops. Originally erected in 1905 by Carl Howelsen and a group of Norwegian skiers living in Chicago, it’s been rebuilt over the years and is still used today. In a curious coincidence, in 1913, the man who loved the mountains and deep snow found his way to the Colorado mountain town we once called our winter home. Although Howelsen returned to Norway in 1922, he left an indelible mark on the town by introducing it to recreational skiing and ski jumping. Not far from the hill named for him, stands a statue of the man known as Flying Norseman. These last few days, I’ve been discussing Paul’s instructions both to carry one another’s burdens and to carry our own loads. In between those two directives, we find a warning about the things that can prevent us from doing that: conceit and comparison.

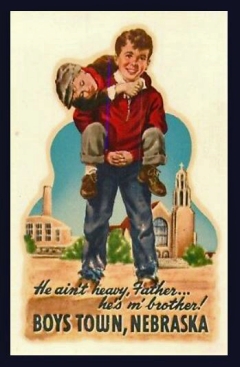

These last few days, I’ve been discussing Paul’s instructions both to carry one another’s burdens and to carry our own loads. In between those two directives, we find a warning about the things that can prevent us from doing that: conceit and comparison. After saying we must carry each other’s burdens, the Apostle Paul seems to reverse himself three sentences later when he tells us we each must carry our own loads. It’s confusing; if we’re all supposed to carry our own loads, then nobody should need help carrying their burdens!

After saying we must carry each other’s burdens, the Apostle Paul seems to reverse himself three sentences later when he tells us we each must carry our own loads. It’s confusing; if we’re all supposed to carry our own loads, then nobody should need help carrying their burdens! Since we tend to think of burdens as demanding and often unwelcome duties or responsibilities, we’re certainly not anxious to take on a burden, especially one that actually belongs to someone else! Yet, that is exactly what we’re told we must do if we are going to fulfill Christ’s mandate. And what is that command? To love one another in the way God loves us.

Since we tend to think of burdens as demanding and often unwelcome duties or responsibilities, we’re certainly not anxious to take on a burden, especially one that actually belongs to someone else! Yet, that is exactly what we’re told we must do if we are going to fulfill Christ’s mandate. And what is that command? To love one another in the way God loves us. In 1 Samuel 15, after Samuel confronts Saul for disobeying God’s clear commands regarding the Amalekites, Saul makes excuses—first by denying his sin, then by justifying his disobedience, and finally by blaming others. It is only after Samuel tells him the consequences of his sin—the loss of his kingship—that Saul reluctantly admits the truth. In contrast, we have Nathan confronting David regarding his sinful behavior with Bathsheba and Uriah. Immediately after the rebuke, David confesses. It would have been easy for David to blame Bathsheba for seducing him, Uriah for hampering his cover-up scheme, or Joab for his part in Uriah’s death, but he didn’t. Acknowledging his guilt, the repentant David confessed.

In 1 Samuel 15, after Samuel confronts Saul for disobeying God’s clear commands regarding the Amalekites, Saul makes excuses—first by denying his sin, then by justifying his disobedience, and finally by blaming others. It is only after Samuel tells him the consequences of his sin—the loss of his kingship—that Saul reluctantly admits the truth. In contrast, we have Nathan confronting David regarding his sinful behavior with Bathsheba and Uriah. Immediately after the rebuke, David confesses. It would have been easy for David to blame Bathsheba for seducing him, Uriah for hampering his cover-up scheme, or Joab for his part in Uriah’s death, but he didn’t. Acknowledging his guilt, the repentant David confessed.