And if someone asks about your hope as a believer, always be ready to explain it. But do this in a gentle and respectful way. Keep your conscience clear. Then if people speak against you, they will be ashamed when they see what a good life you live because you belong to Christ. [1 Peter 3:15b-16 (NLT)]

And if someone asks about your hope as a believer, always be ready to explain it. But do this in a gentle and respectful way. Keep your conscience clear. Then if people speak against you, they will be ashamed when they see what a good life you live because you belong to Christ. [1 Peter 3:15b-16 (NLT)]

In the epistle we know as 1 Peter (written between 60 and 64 AD), the Apostle offered encouragement to early Christians who were encountering persecution for their unorthodox beliefs. Rather than being intimidated by people or afraid of their hostility, Peter counseled them to acknowledge Jesus as the Lord of their lives and ruler of their hearts. Although that acknowledgement was in their hearts, he warned these believers to be ready with their answer should they could be called upon to explain the source of their hope and faith. The Greek word used was apologia which meant a speech in defense and was the term for making a legal defense in court. As if they were in a court of law, Christ’s followers were to be ready with a well-reasoned reply that adequately addressed the issue at hand while doing it in a humble and respectful way. Throughout his letter, the Apostle also addressed the conduct of Christians regarding their relationship with God, government, business, society, family, and the church. He advised his readers to live their lives in a way that would prove their opponents’ accusations unfounded.

I used to wonder how I would answer someone if they wanted to know the reason for my faith or the source of my hope. Should I keep religious tracts in my purse or a couple of pertinent Bible verses handy? I then remembered an old joke about the little boy who asked his father where he came from. The dad hemmed and hawed as he struggled with a rather long-winded and confusing explanation of the birds and bees. When done, the little boy looked at his father quizzically and said, “I was just wondering since Billy says he’s from Baltimore.” As the father learned, sometimes the simplest answer is the best one. If ever asked, the only explanation I’d need is that my hope comes from Jesus, from trusting in God’s promises, and from my conviction that God’s plans for me are for good and not disaster. Moreover, if and when such a question arises, I’m sure the Holy Spirit will be there to put His words in my mouth.

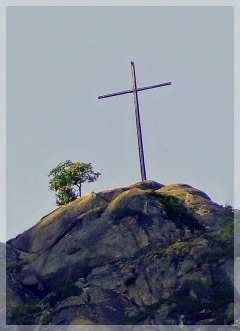

Thinking about Peter’s words, I realize that nobody has ever asked about the source of my hope or reason for my faith. While I’ve had people compliment the little diamond cross I usually wear, no one has ever asked why I wear it. I’ve had people ask where I purchased an outfit, who cuts my hair, what make of shoes I’m wearing, the kind of camera I use, and even the brand perfume I wear. Although I’ve been a walking advertisement for Tommy Bahama, Mimi’s Salon, Naot Shoes, Canon, and Prada’s Infusion d’Iris, I doubt that my devotion to Jesus is as discernable.

Perhaps, instead of worrying about how I would answer a question about the source of my faith, hope or love, I should be more concerned with why I’ve never been asked such a question. I wonder if it’s because, while my appearance (and even my scent) are evident, my faith in Jesus, my hope in God’s promises of forgiveness and salvation, and my love for God and my neighbor aren’t nearly so obvious in the way I conduct my life. They should be!

Starting with the Judaizers who believed that Gentiles first had to be circumcised and conform to Mosaic Law in order to be saved, the early church faced controversy within its ranks. Without a creed, they were challenged with distinguishing between true and false doctrines. Although not written by the Apostles, an early version of what we know as the Apostles’ Creed was probably in use by the last half of the second century. Created to instruct converts and prepare them for baptism, because it didn’t clearly state the nature of Jesus’ divinity or define the relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, doctrinal controversy continued. Along with Gnosticism’s rejection of the incarnation and Marcion’s redefinition of God, there were the Ebionites’ denial of Christ’s divinity, the Arians’ belief that Jesus was neither divine nor eternal, and the Modalists who collapsed the persons of the Trinity into a single person with three types of activity. Rather than destroy the early church, however, these various isms actually did it a favor by forcing it to solidify Christianity’s doctrines.

Starting with the Judaizers who believed that Gentiles first had to be circumcised and conform to Mosaic Law in order to be saved, the early church faced controversy within its ranks. Without a creed, they were challenged with distinguishing between true and false doctrines. Although not written by the Apostles, an early version of what we know as the Apostles’ Creed was probably in use by the last half of the second century. Created to instruct converts and prepare them for baptism, because it didn’t clearly state the nature of Jesus’ divinity or define the relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, doctrinal controversy continued. Along with Gnosticism’s rejection of the incarnation and Marcion’s redefinition of God, there were the Ebionites’ denial of Christ’s divinity, the Arians’ belief that Jesus was neither divine nor eternal, and the Modalists who collapsed the persons of the Trinity into a single person with three types of activity. Rather than destroy the early church, however, these various isms actually did it a favor by forcing it to solidify Christianity’s doctrines. Although many Christian writings refer to Polycarp, only one of his letters remains. Written to the church at Philippi sometime before 150 AD. Polycarp addressed the behavior of a greedy bishop named Valens, explained that true righteousness sprang from true belief, and warned against false teachings. Containing 12 quotes from the Old Testament and 100 quotes or paraphrases from the New, this epistle has been described as a “mosaic of quotations” from the Bible. Using language from what now are known as the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, Acts, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Hebrews, 1 Peter, and 1 and 3 John, his letter is testimony both to the existence of these texts by mid-2nd century and that the early church already believed them to be inspired Scripture.

Although many Christian writings refer to Polycarp, only one of his letters remains. Written to the church at Philippi sometime before 150 AD. Polycarp addressed the behavior of a greedy bishop named Valens, explained that true righteousness sprang from true belief, and warned against false teachings. Containing 12 quotes from the Old Testament and 100 quotes or paraphrases from the New, this epistle has been described as a “mosaic of quotations” from the Bible. Using language from what now are known as the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, Acts, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Hebrews, 1 Peter, and 1 and 3 John, his letter is testimony both to the existence of these texts by mid-2nd century and that the early church already believed them to be inspired Scripture. 1 Timothy doesn’t tell us much about Hymenaeus or Alexander—the men whose faith was shipwrecked. From Paul’s other references to the men, we do know that Hymenaeus denied the doctrine of the resurrection and that Alexander did “much harm” to Paul, but we don’t know the details. Whatever these men said or did, by accusing them of blasphemy and handing them “over to Satan,” Paul seemed to be excommunicating them from the church.

1 Timothy doesn’t tell us much about Hymenaeus or Alexander—the men whose faith was shipwrecked. From Paul’s other references to the men, we do know that Hymenaeus denied the doctrine of the resurrection and that Alexander did “much harm” to Paul, but we don’t know the details. Whatever these men said or did, by accusing them of blasphemy and handing them “over to Satan,” Paul seemed to be excommunicating them from the church. These words were among those the kings of Israel were to copy, keep on their person at all times, and read every day of their lives. Solomon was Israel’s third king and, while we can’t know about Saul or David, it certainly seems that by Solomon’s reign, the words of Deuteronomy had been forgotten or ignored.

These words were among those the kings of Israel were to copy, keep on their person at all times, and read every day of their lives. Solomon was Israel’s third king and, while we can’t know about Saul or David, it certainly seems that by Solomon’s reign, the words of Deuteronomy had been forgotten or ignored.