Cast your cares on the Lord and he will sustain you; he will never let the righteous be shaken. [Psalm 55:22 (NIV)]

Cast all your anxiety on him because he cares for you. [1 Peter 5:7 (NIV)]

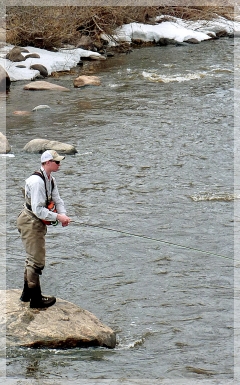

Even though I’m not an angler, whenever I read about casting my cares, I picture using a fly rod and casting my concerns out into the river so the fast moving water can carry them away to God. When we lived in the mountains, one of our favorite walking trails ran alongside the Yampa River and we often paused to watch as the fishermen (and women) cast their lines into the water. Fly fishing is all about the art of casting and a bit like poetry in motion. It was fascinating to watch an angler flick the rod back and forth, gradually increasing the speed of the motion, before finally casting the line forward so the fly would land in the perfect spot. Masquerading as a water insect, the fly is made of things like fur, feathers, fabric and tinsel and secured to a hook. Rather than purchasing flies, many fishermen spend hours tying their own flies. Not wanting to lose either fly or fish in the river, anglers use at least five different knots to securely connect the reel to the backing, fly line, leader, and tippet before finally tying on the fly.

Even though I’m not an angler, whenever I read about casting my cares, I picture using a fly rod and casting my concerns out into the river so the fast moving water can carry them away to God. When we lived in the mountains, one of our favorite walking trails ran alongside the Yampa River and we often paused to watch as the fishermen (and women) cast their lines into the water. Fly fishing is all about the art of casting and a bit like poetry in motion. It was fascinating to watch an angler flick the rod back and forth, gradually increasing the speed of the motion, before finally casting the line forward so the fly would land in the perfect spot. Masquerading as a water insect, the fly is made of things like fur, feathers, fabric and tinsel and secured to a hook. Rather than purchasing flies, many fishermen spend hours tying their own flies. Not wanting to lose either fly or fish in the river, anglers use at least five different knots to securely connect the reel to the backing, fly line, leader, and tippet before finally tying on the fly.

There is an art to fly casting and fly fishermen spend years perfecting their technique, especially since no one cast is ideal for every situation. Christians, however, aren’t casting flies—they’re casting things like fear, problems, anxiety, and worry—the cares every believer faces in this fallen world. While there’s no special technique to casting those cares, like fly fishing, it’s often easier said than done. Just as a fly fisherman may labor over tying his flies and fret about choosing the perfect ones for the day’s conditions, we often spend a great deal of time focusing on our worries rather than casting them into God’s river. Just as the fisherman ties those five knots to keep from losing his fly, we tie ourselves up in knots when we’re reluctant to give up our cares to God!

The anglers casting their lines in the river want to catch and land a fish but, when we cast our cares, we want to bring in an empty line. They catch, we release! Our cares are not for God to take away from us but for us to release to Him. Because the flies on the end of a fishing line are nearly weightless and our cares often seem as heavy as boulders, casting cares seems harder than casting a fly in the river. Nevertheless, it can be done and is far more rewarding than a trophy-sized trout.

Fishermen go to the river with an empty creel and hope to return home with a full one but we go to God with a creel full of cares so we’ll end up with an empty one. Our creels may be empty but we’ll be filled with the peace of God!

He that takes his cares on himself loads himself in vain with an uneasy burden. I will cast my cares on God; he has bidden me; they cannot burden him. [Joseph Hall]

It’s often said that there are no atheists in foxholes. This maxim traces its beginnings back to 1914 and World War 1 when an English newspaper quoted a chaplain at a memorial service for a fallen soldier: “Tell the Territorials and soldiers at home that they must know God before they come to the front if they would face what lies before them. We have no atheists in the trenches. Men are not ashamed to say that, though they never prayed before, they pray now with all their hearts.” When we joined our northern church, it was during the Viet Nam War. I remember a young man in our new member class who’d drawn a low number in the draft lottery. Expecting to be in combat within the year, he confessed wanting to “get right” with God before that time came. Apparently, even the threat of a foxhole is enough to cause some people to rethink their relationship with the Almighty.

It’s often said that there are no atheists in foxholes. This maxim traces its beginnings back to 1914 and World War 1 when an English newspaper quoted a chaplain at a memorial service for a fallen soldier: “Tell the Territorials and soldiers at home that they must know God before they come to the front if they would face what lies before them. We have no atheists in the trenches. Men are not ashamed to say that, though they never prayed before, they pray now with all their hearts.” When we joined our northern church, it was during the Viet Nam War. I remember a young man in our new member class who’d drawn a low number in the draft lottery. Expecting to be in combat within the year, he confessed wanting to “get right” with God before that time came. Apparently, even the threat of a foxhole is enough to cause some people to rethink their relationship with the Almighty.

Many years ago, I was facing a difficult decision about a project. In spite of praying, pondering, searching Scripture for direction, and consulting with wise advisors, I was still in a quandary. Nothing brought me closer to a clear answer to my dilemma. Although it seemed like a good idea (at least in theory) and I felt like I should want to be part of it, doubts kept nagging at me. Wanting God to make known His will, I prayed the words of Psalm 143:10: “Teach me to do your will, for you are my God. May your gracious spirit lead me forward on a firm footing.”

Many years ago, I was facing a difficult decision about a project. In spite of praying, pondering, searching Scripture for direction, and consulting with wise advisors, I was still in a quandary. Nothing brought me closer to a clear answer to my dilemma. Although it seemed like a good idea (at least in theory) and I felt like I should want to be part of it, doubts kept nagging at me. Wanting God to make known His will, I prayed the words of Psalm 143:10: “Teach me to do your will, for you are my God. May your gracious spirit lead me forward on a firm footing.” The anchor, the Christian symbol of hope, is the most prevalent of all the Christian symbols found in the Roman catacombs. In fact, all of the symbols, paintings, mosaics, and reliefs found in the miles of labyrinth-like narrow tunnels and thousands of graves in the catacombs reflect hope in some way. Instead of the dark funereal images you might expect in an underground cemetery, the white walls of the Christian catacombs feature living things like flowers and birds along with Bible stories expressing hope in God’s plan of salvation. Prominent themes from the Old Testament include Daniel emerging untouched from the lions’ den and Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego exiting unharmed from the fiery furnace. Frequently depicted are the stories of Noah, who escaped from the flood, and Jonah who was delivered from the sea monster. Continuing the theme of deliverance are many images of the good shepherd so frequently mentioned in Psalms. New Testament stories usually showed Jesus raising the dead (with over fifty representations of Lazarus), healing people, and feeding the multitude. The art of the catacombs is all about man’s hope in God’s deliverance, provision, and plan of salvation.

The anchor, the Christian symbol of hope, is the most prevalent of all the Christian symbols found in the Roman catacombs. In fact, all of the symbols, paintings, mosaics, and reliefs found in the miles of labyrinth-like narrow tunnels and thousands of graves in the catacombs reflect hope in some way. Instead of the dark funereal images you might expect in an underground cemetery, the white walls of the Christian catacombs feature living things like flowers and birds along with Bible stories expressing hope in God’s plan of salvation. Prominent themes from the Old Testament include Daniel emerging untouched from the lions’ den and Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego exiting unharmed from the fiery furnace. Frequently depicted are the stories of Noah, who escaped from the flood, and Jonah who was delivered from the sea monster. Continuing the theme of deliverance are many images of the good shepherd so frequently mentioned in Psalms. New Testament stories usually showed Jesus raising the dead (with over fifty representations of Lazarus), healing people, and feeding the multitude. The art of the catacombs is all about man’s hope in God’s deliverance, provision, and plan of salvation. My father had what’s often described as a Type-A personality. An impatient workaholic, he always took on more than he could handle. Life, for him, was one crucial task after another, none of which anyone else could do, at least not correctly. Always in a hurry, he never wanted to stop for anything, even when his gas gauge read precariously close to empty. Something more pressing always took precedence over a brief stop for gas. As a result, his car was often left on the roadside while he trudged off with a gas can to find the nearest service station. Instead of saving time, his refusal to stop cost him time. Living that way actually cost him his life; he died of a massive coronary at the age of fifty-six. It’s often been said that your in-box still will be full when you die and, indeed, his was. None of us can accomplish everything on our to-do list and we may well destroy both our relationships and ourselves while trying.

My father had what’s often described as a Type-A personality. An impatient workaholic, he always took on more than he could handle. Life, for him, was one crucial task after another, none of which anyone else could do, at least not correctly. Always in a hurry, he never wanted to stop for anything, even when his gas gauge read precariously close to empty. Something more pressing always took precedence over a brief stop for gas. As a result, his car was often left on the roadside while he trudged off with a gas can to find the nearest service station. Instead of saving time, his refusal to stop cost him time. Living that way actually cost him his life; he died of a massive coronary at the age of fifty-six. It’s often been said that your in-box still will be full when you die and, indeed, his was. None of us can accomplish everything on our to-do list and we may well destroy both our relationships and ourselves while trying.