When you harvest the crops of your land, do not harvest the grain along the edges of your fields, and do not pick up what the harvesters drop. It is the same with your grape crop—do not strip every last bunch of grapes from the vines, and do not pick up the grapes that fall to the ground. Leave them for the poor and the foreigners living among you. I am the Lord your God. [Leviticus 19:9-10 (NLT)]

In a series of negative commands regarding the harvest found in Deuteronomy and Leviticus, we find an ancient form of social justice/economic equity. A landowner was not to return for an overlooked bundle of grain left in the field, olives trees were not to be beaten more than once, grapes vines were not to be repicked after the first fruit was gathered, the edges of the fields were not to be harvested, and any produce dropped by the harvesters or fruit that had fallen or separated from the branch was not to be taken. As the remainders of the harvest, these gleanings were left for the poor.

In a series of negative commands regarding the harvest found in Deuteronomy and Leviticus, we find an ancient form of social justice/economic equity. A landowner was not to return for an overlooked bundle of grain left in the field, olives trees were not to be beaten more than once, grapes vines were not to be repicked after the first fruit was gathered, the edges of the fields were not to be harvested, and any produce dropped by the harvesters or fruit that had fallen or separated from the branch was not to be taken. As the remainders of the harvest, these gleanings were left for the poor.

Immediately following the law about not fully harvesting the crops of the land in Leviticus 19:9-10, we find two more laws: “Do not steal. Do not deceive or cheat one another.” The rabbis interpreted the laws’ juxtaposition to mean that not leaving the gleanings actually was stealing from the poor. Moreover, the poor should not cheat others by taking any more than was necessary.

Although the difference is slight, the landowner didn’t give these gleanings to the poor; he left them. God didn’t ask him to give the gleanings because the harvest wasn’t his to give; the harvest, like everything else, belonged to God! These laws reminded the Israelites that God is the source of their blessings!

We get a picture how this system worked in the Book of Ruth. When widowed and poor Ruth and Naomi return to Bethlehem, Ruth went out to gather grain in the field owned by Boaz. As she walked behind the reapers and gathered whatever was left behind, she was taking what the law said was rightfully hers. When Boaz instructed his workers to pull out some stalks from their bundles and leave them for her, he went over and above the law with an act of charity for the young widow.

1,400 years later, Jesus told the Parable of the Rich Fool—the rich man whose land produced so much that he couldn’t store all of his crops. Deciding to keep the excess for himself, he planned on tearing down his barns to build bigger ones, but he died that very night. The parable pointed out the fleeting nature of wealth and the man’s foolishness in providing for himself when he should have been making provision for his soul. Jesus’ audience, however, would have known the ancient agricultural laws and gotten even more from the story.

Unlike a tithe, God never specified how much of a field should be left uncut; it was a matter between the landowner and the Lord. A man’s generosity could be seen by the amount of field left for the gleaners. Jesus’ listeners probably suspected the man’s extreme wealth was because the uncut edges of his fields were measly (or non-existent), fallen fruit was picked up, or his olives and grapes were double harvested. Jesus’ audience would have thought the greedy landowner more than a fool; they would have thought him a thief who’d kept provisions for the poor to himself!

In a fallen world, there always will be people in need so what do these ancient laws mean to 21st century Christians? In his commentary on the laws of gleaning, 16th century Rabbi Moses Alshikh wrote the following as if it were God speaking: “You shouldn’t think that you are giving to the poor person from your own property, or that I have despised him by not giving bread to him as I have given to you. For he is also my child, just as you are, but his portion is in your produce.” Rather than the edges of our fields, our checkbooks indicate our priorities and, just as it was with the Israelites, that is a matter between us and God. As John Wesley said, the question is, “Not how much of my money will I give to God but how much of God’s money will I keep for myself?”

When one of his congregation suddenly stopped coming to church, a pastor friend asked him about his absence. The man angrily explained that he’d stopped attending because the pastor hadn’t suitably (and publicly) recognized his large donation to the church’s building fund. My friend assured the miffed man that, had the money been given to the pastor for his personal use, he would have thanked him profusely. But, he added, the money hadn’t been given to him; it was given to God! While the church truly appreciated it (and had acknowledged it in his contribution statement), the issue of both the donation and any recognition or thanks really was between the donor and God. A similar experience was shared by a friend who is in charge of the care ministry for her church. One of her volunteers quit because she felt the church had failed to sufficiently appreciate and publicize her service.

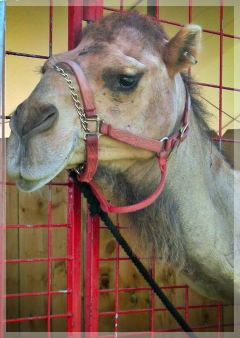

When one of his congregation suddenly stopped coming to church, a pastor friend asked him about his absence. The man angrily explained that he’d stopped attending because the pastor hadn’t suitably (and publicly) recognized his large donation to the church’s building fund. My friend assured the miffed man that, had the money been given to the pastor for his personal use, he would have thanked him profusely. But, he added, the money hadn’t been given to him; it was given to God! While the church truly appreciated it (and had acknowledged it in his contribution statement), the issue of both the donation and any recognition or thanks really was between the donor and God. A similar experience was shared by a friend who is in charge of the care ministry for her church. One of her volunteers quit because she felt the church had failed to sufficiently appreciate and publicize her service. After the rich young ruler departed, Jesus compared the difficulty of a rich man entering heaven to a camel trying to squeeze through the eye of a needle. Because of its impossibility, people find this metaphor troubling. To rationalize it, some scholars speculate that a narrow gate called “The Needle” was located in the wall surrounding Jerusalem. Supposedly used after dark when the main gates were closed, it was so small that a camel had to be unburdened of rider and cargo before getting down on its knees to pass through the gate. They interpret the metaphor as meaning that people must leave behind their baggage, repent, and humble themselves to get through the gate to God’s kingdom. While that’s correct and their explanation makes an excellent Sunday school lesson, no historical or archeological evidence exists that such a gate existed.

After the rich young ruler departed, Jesus compared the difficulty of a rich man entering heaven to a camel trying to squeeze through the eye of a needle. Because of its impossibility, people find this metaphor troubling. To rationalize it, some scholars speculate that a narrow gate called “The Needle” was located in the wall surrounding Jerusalem. Supposedly used after dark when the main gates were closed, it was so small that a camel had to be unburdened of rider and cargo before getting down on its knees to pass through the gate. They interpret the metaphor as meaning that people must leave behind their baggage, repent, and humble themselves to get through the gate to God’s kingdom. While that’s correct and their explanation makes an excellent Sunday school lesson, no historical or archeological evidence exists that such a gate existed.