Each of you, you see, will have to carry your own load. [Galatians 6:5 (NTE)]

After saying we must carry each other’s burdens, the Apostle Paul seems to reverse himself three sentences later when he tells us we each must carry our own loads. It’s confusing; if we’re all supposed to carry our own loads, then nobody should need help carrying their burdens!

After saying we must carry each other’s burdens, the Apostle Paul seems to reverse himself three sentences later when he tells us we each must carry our own loads. It’s confusing; if we’re all supposed to carry our own loads, then nobody should need help carrying their burdens!

A few sentences previous to these verses, however, Paul encourages the Galatian church to follow the Spirit’s lead in their lives and now he’s explaining how walking in the Spirit actually looks—carrying one another’s burdens and carrying our own load. The Greek word Paul used for load was phortion, meaning load or cargo, and it was the word used for a marching soldier’s pack. Paul used the word figuratively to speak of the general responsibilities of life which we all have to bear. Like a soldier’s pack, this load is neither excessively heavy nor difficult to carry. In contrast to the oppressive burden of the Law demanded by the Pharisees, this load is the same phortion Jesus assigned to His followers. Things like discipleship, loving others, and forgiving one another are our load or phortion—obligations for which we alone are responsible.

When Paul wrote of carrying one another’s burdens a few sentences earlier, however, he used the Greek word baros, meaning something extremely heavy. Unlike a soldier’s pack, a baros is a crushing load too heavy for one person to bear alone. Baros was the word Paul used when describing the crushing weight that “was far too heavy for us; it got to the point where we gave up on life itself,” in 2 Corinthians 1:8. It is burdens like his that we are called to carry for one another.

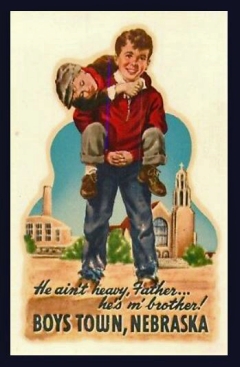

When I was a girl, Christmas seals were sent to us as a method of fundraising by Father Flanagan’s Boys Town. The story behind the picture on those stamps illustrates baros and phortion. A young boy named Howard was abandoned at Boys Town shortly after it opened in 1917. Having had polio, he wore heavy leg braces and couldn’t negotiate the staircases so the bigger boys carried him up and down the stairs. When Father Flanagan asked one of the boys if carrying Howard was hard, the answer was, “He ain’t heavy, Father, he’s my brother!” Years later, those words, accompanied by a photo of the two boys, became the organization’s logo. The burden of going up and down stairs was too great for Howard to bear alone. Because it was a baros, the other boys carried him. On the other hand, Howard was fully capable of doing his school work and helping the younger boys. Had he not done so, he would have failed to carry his own phortion.

While each of us is responsible for fulfilling our Christian duties by carrying our own phortions, one of those duties is to carry another person’s baros! It won’t seem heavy because we’ll be carrying our brother!

Since we tend to think of burdens as demanding and often unwelcome duties or responsibilities, we’re certainly not anxious to take on a burden, especially one that actually belongs to someone else! Yet, that is exactly what we’re told we must do if we are going to fulfill Christ’s mandate. And what is that command? To love one another in the way God loves us.

Since we tend to think of burdens as demanding and often unwelcome duties or responsibilities, we’re certainly not anxious to take on a burden, especially one that actually belongs to someone else! Yet, that is exactly what we’re told we must do if we are going to fulfill Christ’s mandate. And what is that command? To love one another in the way God loves us. Yesterday, I wrote about Jesus’ Parable of the Three Servants, often called the Parable of the Talents. Although I used it as an example of excuse making, that’s not what the parable is about. This parable comes right after Jesus’ description of the end times and the Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids in which He urged readiness for the Day of the Lord. Immediately following this parable about the talents, Jesus spoke about the final judgment. The story of these three servants makes it clear that, when that last day comes, the master will settle accounts: faith will be rewarded and the righteous servants separated from the false ones.

Yesterday, I wrote about Jesus’ Parable of the Three Servants, often called the Parable of the Talents. Although I used it as an example of excuse making, that’s not what the parable is about. This parable comes right after Jesus’ description of the end times and the Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids in which He urged readiness for the Day of the Lord. Immediately following this parable about the talents, Jesus spoke about the final judgment. The story of these three servants makes it clear that, when that last day comes, the master will settle accounts: faith will be rewarded and the righteous servants separated from the false ones.

When Robert Louis Stevenson was just a boy, he was gazing out the window one evening and saw the lamplighter lighting the street lights. The future poet is reported to have said, “Look, Nanny! That man is putting holes in the darkness.” While it makes for a good sermon illustration, a more accurate version of his words is found in an essay he wrote in 1878, “A Plea for Gas Lamps,” in which the man expressed his opposition to the “ugly blinding glare” of the electric lights that were beginning to replace the gas lamps of Edinburgh. After asking God to bless the lamplighter, the poet described him as “speeding up the street and, at measured intervals, knocking another luminous hole into the dusk.” The lamplighter, said Stevenson, “distributed starlight, and, as soon as the need was over, re-collected it.”

When Robert Louis Stevenson was just a boy, he was gazing out the window one evening and saw the lamplighter lighting the street lights. The future poet is reported to have said, “Look, Nanny! That man is putting holes in the darkness.” While it makes for a good sermon illustration, a more accurate version of his words is found in an essay he wrote in 1878, “A Plea for Gas Lamps,” in which the man expressed his opposition to the “ugly blinding glare” of the electric lights that were beginning to replace the gas lamps of Edinburgh. After asking God to bless the lamplighter, the poet described him as “speeding up the street and, at measured intervals, knocking another luminous hole into the dusk.” The lamplighter, said Stevenson, “distributed starlight, and, as soon as the need was over, re-collected it.” When Alexander the Great’s army was advancing on Persia, his troops were so weighted down by the spoils of war they’d taken in earlier campaigns that they moved too slowly to be effective in combat. At one critical point, it seemed that defeat was inevitable. As much as the greedy Alexander desired the silver, gold, and other treasures they’d pillaged, he ordered that all the plunder be thrown into a heap, burned, and left behind. Although his troops complained bitterly, they did as directed. Once unencumbered by the excess weight of their treasure, his army saw the wisdom of Alexander’s command when their campaign turned from impending defeat to victory. “It was as if wings had been given to them—they walked lightly again,” said one historian.

When Alexander the Great’s army was advancing on Persia, his troops were so weighted down by the spoils of war they’d taken in earlier campaigns that they moved too slowly to be effective in combat. At one critical point, it seemed that defeat was inevitable. As much as the greedy Alexander desired the silver, gold, and other treasures they’d pillaged, he ordered that all the plunder be thrown into a heap, burned, and left behind. Although his troops complained bitterly, they did as directed. Once unencumbered by the excess weight of their treasure, his army saw the wisdom of Alexander’s command when their campaign turned from impending defeat to victory. “It was as if wings had been given to them—they walked lightly again,” said one historian.