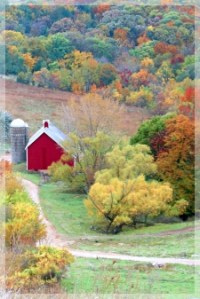

Let the heavens be glad, and the earth rejoice! Let the sea and everything in it shout his praise! Let the fields and their crops burst out with joy! Let the trees of the forest sing for joy. [Psalm 96:11-12 (NLT)]

In Letters to Malcom, C. S. Lewis wrote, “We, or at least I, shall not be able to adore God on the highest occasions if we have learned no habit of doing so on the lowest. … Any patch of sunlight in a wood will show you something about the sun which you could never get from reading books on astronomy. These pure and spontaneous pleasures are ‘patches of Godlight’ in the woods of our experience.”

In Letters to Malcom, C. S. Lewis wrote, “We, or at least I, shall not be able to adore God on the highest occasions if we have learned no habit of doing so on the lowest. … Any patch of sunlight in a wood will show you something about the sun which you could never get from reading books on astronomy. These pure and spontaneous pleasures are ‘patches of Godlight’ in the woods of our experience.”

What Lewis called “patches of Godlight,” I think of as God’s grace notes. In music, a grace note is played with a light quick motion that immediately leads to the principle and stressed note. Unnecessary for the melody and so brief they don’t alter the tempo, grace notes merely enrich the music by adding a small embellishment. Like the musical grace note and Lewis’s “patches of Godlight,” God’s grace notes aren’t necessary; nevertheless, they enhance our lives. They’re subtle reminders that God is present and loves us enough to embellish the day with a little something extra.

Unlike Kodak moments, Godlight and grace notes are not meant to be saved. They’re rarely repeated and we can’t predict when a “patch of Godlight” will shine into our lives or a grace note will play. While waiting at a red light, I glanced at the grassy median to my left where small yellow flowers appeared to be dancing in the air. Although hundreds of dainty Sulphur butterflies were flitting to and fro just a few inches above the yellow wireweed in the grass, it looked like the flowers’ petals had escaped from their stems and the field was bursting with joy! Did God arrange that revelry in yellow just for me? Probably not, but it felt like He did and my day changed for the better because of it.

After noticing that others at that light seemed oblivious to the butterfly frolic, I wondered how many of God’s grace notes I’ve missed because I wasn’t looking or listening. As the prophet Elijah learned, God doesn’t necessarily reveal Himself in spectacular displays of things like lightning, wind, thunder, and fire. Our infinitely creative God whispers through the ordinary as well—with things as mundane as yellow butterflies, a child’s laughter, the aroma of jasmine, a finch on the windowsill, a song on the radio, seeing a young couple caress or an old couple walk hand in hand, a shooting star, a stranger’s smile, or a patch of sunlight while walking through the woods. Although God personalizes His grace notes for each one of us, we need to slow down and be mindful enough to recognize and appreciate them.

There is an old Hindi poem, translated by Ravindra Kumar Karnani, in which a child asks God to reveal Himself. God responds with a meadowlark’s song, then the roar of thunder, followed by a star, and the birth of a baby. In her ignorance, however, the child doesn’t recognize any of God’s answers. Finally, in desperation, she cries, “Touch me God, and let me know you are here!” But, when God touches the child, she brushes off the butterfly and walks away disappointed. It occurs to me that we are not much different from her. May we never thoughtlessly brush away one of God’s gentle kisses, fail to notice His grace notes, or miss appreciating a small patch of Godlight!

Are we paying attention to the everyday moments of our lives and seeing God in them, or are we living in such a chaotic frenzy that we hope we’ll have time to look for the presence and mystery of God later, when we have more time – say, when the degree is finished, the kids have moved out, this project is completed, or we retire? [Dean Nelson]

Because the pastor’s sermon was about being thankful, she’d selected “Come, Ye Thankful People, Come” as the evening’s opening hymn. Henry Alford wrote this hymn in 1844 for village harvest festivals in England called Harvest Home. Rural churches would celebrate the harvest by decorating with pumpkins and autumn leaves, collecting the harvest bounty, and then distributing it to the needy. Because of its seasonal harvest imagery, we usually sing this hymn in November at Thanksgiving but this was mid-July! Reading the hymn’s words out of their traditional Thanksgiving context, I understood their meaning in an entirely different way.

Because the pastor’s sermon was about being thankful, she’d selected “Come, Ye Thankful People, Come” as the evening’s opening hymn. Henry Alford wrote this hymn in 1844 for village harvest festivals in England called Harvest Home. Rural churches would celebrate the harvest by decorating with pumpkins and autumn leaves, collecting the harvest bounty, and then distributing it to the needy. Because of its seasonal harvest imagery, we usually sing this hymn in November at Thanksgiving but this was mid-July! Reading the hymn’s words out of their traditional Thanksgiving context, I understood their meaning in an entirely different way. “Happy Easter,” said the Pastor as she welcomed us to worship. She was neither a week late nor four weeks early for Greek Orthodox Easter. While it’s no longer Easter Sunday and all the jelly beans, chocolate bunnies, and hard-boiled eggs have been eaten, it is Eastertide (“tide” just being an old-fashioned word for “season” or “time”). The Christian or liturgical calendar designates Eastertide as the fifty days from Easter/Resurrection Sunday to Pentecost (when we celebrate the outpouring of the Holy Spirit and the birth of the church).

“Happy Easter,” said the Pastor as she welcomed us to worship. She was neither a week late nor four weeks early for Greek Orthodox Easter. While it’s no longer Easter Sunday and all the jelly beans, chocolate bunnies, and hard-boiled eggs have been eaten, it is Eastertide (“tide” just being an old-fashioned word for “season” or “time”). The Christian or liturgical calendar designates Eastertide as the fifty days from Easter/Resurrection Sunday to Pentecost (when we celebrate the outpouring of the Holy Spirit and the birth of the church). During Lent, I journeyed toward Jesus’ death and resurrection with a Lenten devotional. For each of the season’s forty days, there was a Scripture reading from John, a short devotional, an inspiring quote, interesting facts about Lent’s history, and a unique fast for the day. Each day’s reading also provided journaling space for the reader. For the fortieth day’s journal entry, readers were asked to write a brief letter of thanks to Jesus for all He endured to lead them into eternal life.

During Lent, I journeyed toward Jesus’ death and resurrection with a Lenten devotional. For each of the season’s forty days, there was a Scripture reading from John, a short devotional, an inspiring quote, interesting facts about Lent’s history, and a unique fast for the day. Each day’s reading also provided journaling space for the reader. For the fortieth day’s journal entry, readers were asked to write a brief letter of thanks to Jesus for all He endured to lead them into eternal life. It was the week before the Passover and Jerusalem was teeming with pilgrims who’d come for the celebration. News of the rabbi who’d brought Lazarus back to life was spreading through the crowd. As the people prepared to celebrate their deliverance from slavery in Egypt, they hoped for the promised Messiah who would deliver them from the tyranny of Rome. Could Jesus be the one to do that?

It was the week before the Passover and Jerusalem was teeming with pilgrims who’d come for the celebration. News of the rabbi who’d brought Lazarus back to life was spreading through the crowd. As the people prepared to celebrate their deliverance from slavery in Egypt, they hoped for the promised Messiah who would deliver them from the tyranny of Rome. Could Jesus be the one to do that? “He’d always looked at religion as a crutch for people who were too scared to do life by themselves,” is the way author Chris Fabry described a character in his book June Bug. That description made me think of Karl Marx’s frequently paraphrased statement: “Religion is the opium of the people.” Sigmund Freud had an equally low opinion of religion and described it as a form of wish fulfillment. Thinking of religion as little more than a man-made coping mechanism for dealing with the harsh realities of life, Fabray’s character, Marx, and Freud disparaged it along with things like crutches and pain relievers.

“He’d always looked at religion as a crutch for people who were too scared to do life by themselves,” is the way author Chris Fabry described a character in his book June Bug. That description made me think of Karl Marx’s frequently paraphrased statement: “Religion is the opium of the people.” Sigmund Freud had an equally low opinion of religion and described it as a form of wish fulfillment. Thinking of religion as little more than a man-made coping mechanism for dealing with the harsh realities of life, Fabray’s character, Marx, and Freud disparaged it along with things like crutches and pain relievers.