This is my commandment: Love each other in the same way I have loved you. There is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. [John 15:12-13 (NLT)]

While every thesaurus says that hate is the opposite of love, I’m not so sure. Authors like Wilhelm Stekel, John Le Carré, Rollo May, Elie Wiesel, and George Bernard Shaw have said that indifference (or apathy) is the opposite of love. Disagreeing, Reverend Billy Graham said the opposite of love is selfishness.

While every thesaurus says that hate is the opposite of love, I’m not so sure. Authors like Wilhelm Stekel, John Le Carré, Rollo May, Elie Wiesel, and George Bernard Shaw have said that indifference (or apathy) is the opposite of love. Disagreeing, Reverend Billy Graham said the opposite of love is selfishness.

Hate, apathy, or selfishness? Since apathy is lack of concern or interest in anything and selfishness is lack of concern or interest in anything but oneself, I thought back to Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan. Although its purpose was to define the identity of one’s “neighbor” to the lawyer who asked, the parable also illustrates what it means to love.

Let’s start with the bandits. They probably didn’t hate the man they attacked and, had they simply been indifferent to him, they would have ignored him. While they weren’t interested in his well-being, they were very interested his property and they wanted it. Rather than hate or apathy, it was selfishness that made them take everything the man possessed. Their self-centered attitude was “What’s yours is mine, and I’ll take it!”

We then come to the priest and Levite. We have no reason to suspect they knew the victim and hated him. But, had they truly been disinterested, the priest wouldn’t have crossed to the other side of the road upon seeing the wounded man nor would the Levite deliberately have walked over to look at him. Both men took an interest in the wounded man and then deliberately chose to ignore him. Rather than hate-filled or apathetic, they refused to help the man out of selfishness. More concerned about themselves and their journey than the welfare of a dying man along the side of the road, their self-centered attitude was, “What’s mine is mine, and I’m going to keep it.”

Then we come to the Samaritan. As a Samaritan, he certainly had reason to hate the Jewish victim, but he didn’t. Rather than being indifferent to the man’s condition or selfish with his time and resources, he was generous. His philosophy was that of love: “What’s mine is yours and I will share it.”

When thinking of hate or even apathy as the opposite of love, like the priest and Levite, we can tell ourselves that, as long as we didn’t hurt someone, we obeyed the command to love. But, when we think of selfishness as the opposite of love, far more is asked of us. No longer passive, love demands more than simply not hating or harming someone. Love requires effort; it is a giving up of self and a giving of self to another.

After writing that selfishness was the opposite of love, Billy Graham asked, “Will you ask the Holy Spirit to free your life from selfishness and fill you instead with His love?” Will you?

The first question which the priest and the Levite asked was: “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” but the good Samaritan reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” [Martin Luther King, Jr.]

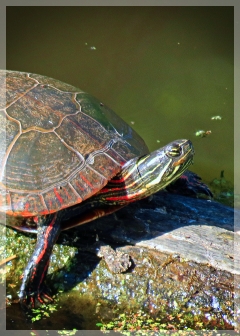

Once upon a time, a father gave his daughter a painted turtle. One morning, she ran to her father in tears and sobbed, “My turtle died!” Wanting to bring a smile back to his little girl’s face, Dad promised the reptile a lovely funeral after which he’d take her to their favorite fast-food spot for a happy meal and toy. When that did nothing to stop the flow of tears, he upped the ante by proposing to follow lunch with the latest Disney princess movie. As the sobbing slowed, he then promised they’d stop at the mall where she could ride on the merry-go-round and Ferris wheel. With only a few whimpers remaining, Dad topped off his offer with a promise to stop on the way home for a double scoop ice cream cone. Thrilled to finally see a smile on his daughter’s face, the relieved father reached into the tank to remove the dead turtle only to discover that it was alive and well and just had been enjoying a turtle nap. When he joyfully reported, “He’s not dead!” the disappointed girl’s response was, “Then can we kill it?”

Once upon a time, a father gave his daughter a painted turtle. One morning, she ran to her father in tears and sobbed, “My turtle died!” Wanting to bring a smile back to his little girl’s face, Dad promised the reptile a lovely funeral after which he’d take her to their favorite fast-food spot for a happy meal and toy. When that did nothing to stop the flow of tears, he upped the ante by proposing to follow lunch with the latest Disney princess movie. As the sobbing slowed, he then promised they’d stop at the mall where she could ride on the merry-go-round and Ferris wheel. With only a few whimpers remaining, Dad topped off his offer with a promise to stop on the way home for a double scoop ice cream cone. Thrilled to finally see a smile on his daughter’s face, the relieved father reached into the tank to remove the dead turtle only to discover that it was alive and well and just had been enjoying a turtle nap. When he joyfully reported, “He’s not dead!” the disappointed girl’s response was, “Then can we kill it?”

When writing about the Good Samaritan yesterday, I recalled being asked who represents Jesus in the parable. The most obvious answer appears to be the Samaritan. After all, love that unlimited and sacrificial had to have been supernatural. The parallels are somewhat obvious—both men were merciful, compassionate, paid another man’s debt, promised to return, and were despised and rejected by the Jews. In fact, early commentators like Irenaeus, Clement, Augustine, and Origen found all sorts of allegorical meaning in the story with the injured man representing Adam, the bandits Satan, the loss of clothing as man’s loss of innocence, the wine given the man as Christ’s atoning blood, the inn as the Church, the innkeeper as Paul (or the Pope), and the two coins given to the innkeeper as the Law and the Prophets or the two testaments. While some of Jesus’ parables (like the Sower and the Soils, the Wheat and the Weeds, and the Evil Tenants) clearly are allegories, other are not.

When writing about the Good Samaritan yesterday, I recalled being asked who represents Jesus in the parable. The most obvious answer appears to be the Samaritan. After all, love that unlimited and sacrificial had to have been supernatural. The parallels are somewhat obvious—both men were merciful, compassionate, paid another man’s debt, promised to return, and were despised and rejected by the Jews. In fact, early commentators like Irenaeus, Clement, Augustine, and Origen found all sorts of allegorical meaning in the story with the injured man representing Adam, the bandits Satan, the loss of clothing as man’s loss of innocence, the wine given the man as Christ’s atoning blood, the inn as the Church, the innkeeper as Paul (or the Pope), and the two coins given to the innkeeper as the Law and the Prophets or the two testaments. While some of Jesus’ parables (like the Sower and the Soils, the Wheat and the Weeds, and the Evil Tenants) clearly are allegories, other are not. Operating on a salvation by works mentality, the lawyer/expert in Mosaic law asked what he needed to do to inherit eternal life. When Jesus asked what the law said, the man cited Deuteronomy 6:5, about total devotion to God, and Leviticus 19:18, about loving his neighbor as himself. When Jesus told him, “Do this, and you will live,” the man realized that perfect obedience to loving everyone wasn’t possible. Hoping to limit the commandment to something more attainable, he searched for a loophole and asked, “Who is my neighbor?” Perhaps he was thinking of the words found in the book of Sirach (a collection of moral counsel and maxims well known in Jesus’ time), “If you do a kindness, know to whom you do it, and you will be thanked for your good deeds. … Give to the godly man, but do not help the sinner.” [12:1,4] These words reflected the prevailing view of the time that kindheartedness and aid were mainly for family, friends, or a righteous deserving person, but certainly not to one’s enemies.

Operating on a salvation by works mentality, the lawyer/expert in Mosaic law asked what he needed to do to inherit eternal life. When Jesus asked what the law said, the man cited Deuteronomy 6:5, about total devotion to God, and Leviticus 19:18, about loving his neighbor as himself. When Jesus told him, “Do this, and you will live,” the man realized that perfect obedience to loving everyone wasn’t possible. Hoping to limit the commandment to something more attainable, he searched for a loophole and asked, “Who is my neighbor?” Perhaps he was thinking of the words found in the book of Sirach (a collection of moral counsel and maxims well known in Jesus’ time), “If you do a kindness, know to whom you do it, and you will be thanked for your good deeds. … Give to the godly man, but do not help the sinner.” [12:1,4] These words reflected the prevailing view of the time that kindheartedness and aid were mainly for family, friends, or a righteous deserving person, but certainly not to one’s enemies. The book of Nehemiah opens with Nehemiah’s distress at learning that Jerusalem’s walls remained in shambles even though decades had passed since the first Jewish exiles returned to the city. Broken walls and no gates meant Jerusalem (and the Temple) were defenseless against enemies and wild animals. Just as a city is defenseless against its enemies’ attacks, a person without self-control is defenseless against the Satan’s attacks.

The book of Nehemiah opens with Nehemiah’s distress at learning that Jerusalem’s walls remained in shambles even though decades had passed since the first Jewish exiles returned to the city. Broken walls and no gates meant Jerusalem (and the Temple) were defenseless against enemies and wild animals. Just as a city is defenseless against its enemies’ attacks, a person without self-control is defenseless against the Satan’s attacks.