You shall not steal. [Exodus 20:15 (ESV)]

Jesus once said that Satan was a thief. Satan does not steal money, for he knows that money has no eternal value. He steals only what has eternal value—primarily the souls of men. [Zac Poonen]

The patient Cormorant had been diving and resurfacing empty-beaked for several minutes before finally emerging victorious with a large fish crosswise in its beak. The fish thrashed in the cormorant’s beak while the bird tried to re-position its meal so it could be swallowed head first. A Brown Pelican suddenly crashed into the water and, after a great deal of wing flapping and water splashing, it was clear the Cormorant was no match for the larger bird. While the Pelican threw back its head and swallowed the unlucky fish, the unfortunate cormorant swam away still hungry.

The patient Cormorant had been diving and resurfacing empty-beaked for several minutes before finally emerging victorious with a large fish crosswise in its beak. The fish thrashed in the cormorant’s beak while the bird tried to re-position its meal so it could be swallowed head first. A Brown Pelican suddenly crashed into the water and, after a great deal of wing flapping and water splashing, it was clear the Cormorant was no match for the larger bird. While the Pelican threw back its head and swallowed the unlucky fish, the unfortunate cormorant swam away still hungry.

Apparently, food theft (kleptoparasitism) is common among birds and it’s not limited to stealing one another’s fish dinner. Some species harass other birds until they spit up swallowed food and several species conduct high-speed chases in the sky and grab food from other birds in midair. Bird theft isn’t even limited to food. Blue Jays and Black Crows frequently pilfer the nests of other birds for shiny things with which to adorn their own nests while Magpies and Eagles will steal building material as well. At first, it seems like the birds are exploiting the hard work of others but they’re just doing what birds do naturally. Living in a competitive world with limited resources, they’ve developed remarkable skills needed for survival.

Fortunately, we don’t have to steal fish or mice from another person’s mouth or snatch bits of foil, moss, or twigs from someone’s home to survive. Unlike the birds and other animals, God created us in His image. As such, He gave us a different set of rules for living. Nevertheless, the Pelican’s behavior caused me to consider the simple commandment not to steal—a prohibition important enough to be mentioned numerous times throughout the Bible. Is this commandment limited to things like not cheating on taxes, shop lifting, snatching purses, embezzling, and robbing banks or is there something more?

Essentially, most of us are honest; nevertheless, we steal—by using worktime to check social media or personal email, padding an expense account, getting paid under the table, taking more than our share, or cutting in line. We’re stealing when we do a slip-shod job and call it “good enough,” fail to return something borrowed or found, pay unfair wages, or take advantage of someone else’s hardship, kindness, or ignorance. We steal the truth whenever we tell a lie and steal God’s glory when we take credit for His blessings. We rationalize our little cheats and don’t think of them as stealing, but they are.

Worse, we can steal someone’s reputation when we gossip, we can steal their hope when we deny them an opportunity or encouragement, we can steal their joy with a few poorly chosen words, and we can steal their dignity when we treat them in a demeaning manner. When we snub, humiliate, abuse, deny, and ignore or when we’re over-bearing, selfish, rude, negative, and unforgiving, we’re stealing something far more valuable than money. We’re stealing things like self-respect, innocence, courage, delight, confidence, dreams, and opportunities. This sort of stealing is neither a misdemeanor nor a felony; nevertheless, it is a sin.

A century of dike-building, agricultural development, and population growth has destroyed much of Florida’s wetlands and threatened the survival of dozens of animals like Florida panthers, Snail Kites, and Wood Storks. The White Ibis, however, is an exception. Having adapted to the new urban landscape, large groups of ibis happily graze the lawns of subdivisions, parks, and golf courses. They’ve found it easier to poke at the soil for a predictable buffet of grubs, earthworms, and insects than to forage in the remaining wetlands for aquatic prey like small fish, frogs, and crayfish. Once wary of humans, these urbanized ibis pay little or no attention to people as they follow one another across our lawns.

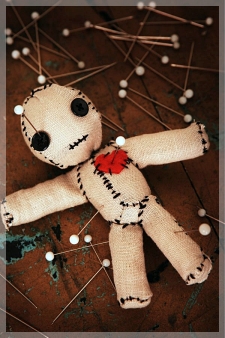

A century of dike-building, agricultural development, and population growth has destroyed much of Florida’s wetlands and threatened the survival of dozens of animals like Florida panthers, Snail Kites, and Wood Storks. The White Ibis, however, is an exception. Having adapted to the new urban landscape, large groups of ibis happily graze the lawns of subdivisions, parks, and golf courses. They’ve found it easier to poke at the soil for a predictable buffet of grubs, earthworms, and insects than to forage in the remaining wetlands for aquatic prey like small fish, frogs, and crayfish. Once wary of humans, these urbanized ibis pay little or no attention to people as they follow one another across our lawns. Without a globe, I allowed a random number to decide the nation for which I’d pray this week. Number 19 was Benin and I’m embarrassed to admit knowing nothing about this narrow strip of land in West Africa between Nigeria and Togo. These three nations once were part of the kingdom of Dahomey and it was in Dahomey that the ancient practice of voudon/vodun/vodou (commonly called voodoo) began. Now a republic, Benin is a severely underdeveloped nation, rife with corruption, where the life expectancy for men is just 60! A little over 40% of the population are Christian, nearly 30% Muslim, about 17% practice voodoo, and another 10% follow other indigenous/animistic religions. As a side note, ARDA (The Association for Religion Data Archives) stated that many of those identifying as Christian also practice voodoo.

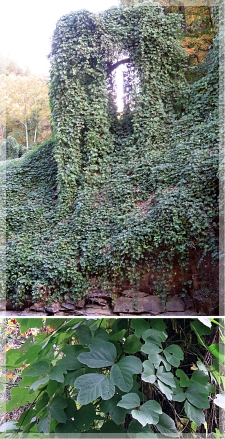

Without a globe, I allowed a random number to decide the nation for which I’d pray this week. Number 19 was Benin and I’m embarrassed to admit knowing nothing about this narrow strip of land in West Africa between Nigeria and Togo. These three nations once were part of the kingdom of Dahomey and it was in Dahomey that the ancient practice of voudon/vodun/vodou (commonly called voodoo) began. Now a republic, Benin is a severely underdeveloped nation, rife with corruption, where the life expectancy for men is just 60! A little over 40% of the population are Christian, nearly 30% Muslim, about 17% practice voodoo, and another 10% follow other indigenous/animistic religions. As a side note, ARDA (The Association for Religion Data Archives) stated that many of those identifying as Christian also practice voodoo. Last month we took a driving trip through Virginia and North Carolina to enjoy the fall colors in the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains. While taking a train ride along the Nantahala River Gorge, we commented on the beautiful vines covering the hillside. Our seat-mate told us this lovely looking plant is a destructive weed called kudzu. Native to Asia, this semi-woody vine was introduced to the U.S. back in 1876 during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Originally advertised as an ornamental plant, kudzu’s ability to grow up to a foot day (and up to 60-feet a year), overtake, grow over, and smother just about anything in its path, has given it a new name: “the vine that ate the South.”

Last month we took a driving trip through Virginia and North Carolina to enjoy the fall colors in the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains. While taking a train ride along the Nantahala River Gorge, we commented on the beautiful vines covering the hillside. Our seat-mate told us this lovely looking plant is a destructive weed called kudzu. Native to Asia, this semi-woody vine was introduced to the U.S. back in 1876 during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Originally advertised as an ornamental plant, kudzu’s ability to grow up to a foot day (and up to 60-feet a year), overtake, grow over, and smother just about anything in its path, has given it a new name: “the vine that ate the South.” Most trees begin life as a seed in the soil of the forest floor and most trees also observe proper forest etiquette by not killing one another. The strangler fig (Ficus aurea), however, is not your typical tree. Rather than starting in the soil where the fig’s seeds would struggle to germinate in the darkness of the dense forest’s floor, strangler figs usually begin life high up in the forest’s canopy. Blown there by the wind or deposited by animals in their droppings, the sticky fig seed usually begins its life in the bark crevices of a mature tree.

Most trees begin life as a seed in the soil of the forest floor and most trees also observe proper forest etiquette by not killing one another. The strangler fig (Ficus aurea), however, is not your typical tree. Rather than starting in the soil where the fig’s seeds would struggle to germinate in the darkness of the dense forest’s floor, strangler figs usually begin life high up in the forest’s canopy. Blown there by the wind or deposited by animals in their droppings, the sticky fig seed usually begins its life in the bark crevices of a mature tree. Effortlessly skimming over the water, the bird occasionally dipped its bill into the water before gracefully rising, circling the pond, and returning to skim along the water again. Even though I’d never seen one inland, the bird’s large bill, distinctive black and white coloring, and unique flight identified it as a black skimmer. Although skimmers usually spend their lives around sandy beaches and coastal islands, sometimes they feed in inland lakes during nesting season and I was thrilled to watch several skimming over our lake just before sunrise.

Effortlessly skimming over the water, the bird occasionally dipped its bill into the water before gracefully rising, circling the pond, and returning to skim along the water again. Even though I’d never seen one inland, the bird’s large bill, distinctive black and white coloring, and unique flight identified it as a black skimmer. Although skimmers usually spend their lives around sandy beaches and coastal islands, sometimes they feed in inland lakes during nesting season and I was thrilled to watch several skimming over our lake just before sunrise.